LONG RANGE STUDIO VISITS

Sebastian Reis and Sam Van Strien

This conversation from the Long Range Studio Visits series brings together two artists working with unconventional image formats. They discuss the shift in working conditions during lockdown, the ways they are influenced by architecture and found objects, and the strategies in which they develop their works.

Sam van Strien is a visual artist driven by the question of how – and where – we experience architecture. He is interested in examining how we see, experience and interpret the architecture around us, and how his work complicates this relationship for the viewer. His work engage with these questions through both his direct and mediated experiences. This results in works that use rubbings of architecture, and the photographs and texts that he finds in architects' archives.

The genesis of images and objects, along with their function of representation, is the focus of Sebastian Reis’ art making. He is approaching this by wondering if myth – that has been traditionally assigned to and associated with the visual arts – is still a feasible possibility in contemporary culture and how an incorporation of this ancient idea might be achieved. Reis is working mostly with painting, photography and objects. In doing so, he is interested in finding different and new ways of combining these elements.

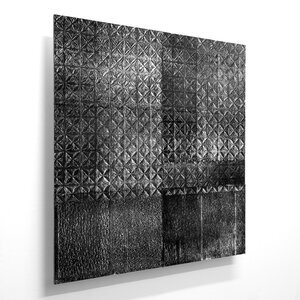

Sebastian Reis, Exhibition View, I was told there would be cake, Project Room, Helsinki, 2017

SvS: Hello Sebastian, it’s great to be introduced to you and your work through PADA. Our work seems to have a lot of related concerns and interests.

In your practice you use analogue and digital photography to engage with ideas surrounding representation. You work at different scales, from work that is quite intimate and precious, up to the dimensions of a body or a room. What choices do you make when determining the scale of your work? Have you been adapting this during lockdown, given the potential limits of space when working from home.

SR: Hi Sam! It is really nice to have this conversation about our practices. There seem to be some very interesting overlapping elements within our works. Representations and their presence is one of the main interests within my work. That also seems to be a concern in your work? In the beginning, when I worked mainly with photography, I was wondering what size actually means in a photographic print, especially if you have endless possibilities for enlarging them. What is the final choice? Where does the decision come from? Is it only convention?

When I used analogue photo materials I mostly printed them in the size of the negatives because that seemed back then the only true solution. Out of this evolved a deep interest in 1-1 scales – and in bringing the reproduction and source next to each other.

In my current work, where I use a variety of materials, it really depends. I am much less rigid and try to play with scales. I am more interested in the experience and curiosity towards them. How does it feel if something tiny becomes monumental, yet it is still fragile? The lockdown didn’t really have any impact concerning scales.

The approach of the frottages or rubbings that you are using is bound to the “original” size. There are a lot of patterns in your work. Can you tell me a bit more about how you make choices in terms of where the surfaces start and end? Do you have any “rules” for (re-)arranging them?

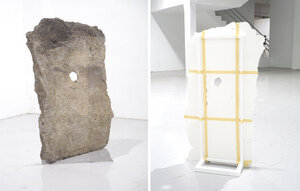

Sam Van Strien, studio shot

SvS: Representations and their presence is a concern that we both share in our work, especially in relation to the mediums of photography and rubbings, and how they can be used to create a document or trace of a physical environment.

The choices I make in terms of where I make my rubbings depends on the context. In my series, A Pattern Language, I wanted to focus on the compositional and formal elements of the azulejo tile, specifically the point at which two architectural surfaces meet, such as a tile adjoining a brick.

The beginning and edge of my work is determined by many factors such as time, the dimensions of my paper, and even the weather. I make rubbings year round, and as you can imagine, weather does affect how long I can work outside. Often I have to negotiate with building security as well, especially if it’s a corporate building. That impacts where the work is positioned and the amount of time I have to make a rubbing.

Through my process and the resulting work I attempt to understand the character of a building, whether that is its context and history, or its material qualities. The rubbings are a mediated experience of the building, and my rubbings are an attempt at representing this character.

My hope is that even though my rubbings are defined by an edge and a physical limit, they might suggest something that continues beyond the edge of the paper, whether that be a pattern or a texture.

SR: One reference that comes immediately to my mind is the Boyle Family, who made castings of different grounds and painted them in high detail. Even though – as far as I remember – they chose the sources rather randomly, there are a lot of patterns and construction materials present in their works. However, the Boyle Family’s works are three dimensional surfaces. Obviously through your approach, you make use of the structure of a material, but then you translate this back into an image. I think, there again, our approaches have something very interesting in common. In more recent times, I’ve given my images their own structure so that they can gain independence.

You talk about limitations and their effects on your work: time, weather, materials. Does it sometimes bother you that you are so depending on these factors? I am thinking especially of the last couple of months, where our radius of movement has been very limited.

SvS: I definitely get frustrated by these factors, especially at the moment. But I enjoy moving between different ways of working, whether that be in the studio, reading and researching, or walking outside in the city.

Since lockdown I’ve been working on graphite drawings that use archival images of corporate buildings. I’m interested in how corporate buildings are documented by photographers, which are often commissioned by the architects of a building. I’ve also been working on older drawings that I’d been wanting to eventually return to. It’s been quite refreshing to make work on a desk space again and to develop a part of my practice that is quite distinct from what I usually make.

I can definitely see that your images have their own structure independent from their source material. How do you decide upon the dimensions of the sheets of paper that form your completed works? I’m interested in how your work has seams between the sheets of paper. Do you want to keep your work seamless, or are you interested in the potential errors and overlaps when putting together the work? I’m particularly interested in the irregularities that occur in my work when individual sheets are placed together.

How does using an analogue or digital camera inform the choices you make in your work? I can imagine the decisions printing in a darkroom is quite different from printing a digital photograph, given the possibilities and limitations between these technologies. Does digital photography give you more freedom, or do you create a system for working with that specific technology?

Sebastian Reis, Work in Progress, Studio View, June 2020

SR: I agree, I think it is always very refreshing to have several different practices to go back to. Are there any types of corporate buildings especially interesting to you? What does it mean for you to translate the archival photos back to drawings, where you have the possibility to change details or even “alter” the architecture?

Another thought that occurs is your interest in the “micro-” and “macro-” level of the buildings. On the one hand you have the 1-1 details, and on the other hand you have the building as defined by architectural photographers. How important is it for you, when you work with archival images, that you experience the buildings yourself, for example to see what positions the photos have been taken?

By independence, I also mean that my works can escape from being a “conventional” image and can move in a space easily. They have the potential to become a different experience, even though they still are very much images. Usually, I start with A3 prints that I cut apart and tape together. Because I do not use the prints directly, but their transfers, a variety of errors like missing parts, distortions, and other imperfections occur. These become an important part of the final work. They then blend in by being overpainted or replaced in part. I’m very interested in these irregularities, especially because the human eye is only capable of seeing them when the image is closely examined.

I understand digital and analogue photography as two different tools, with very different systems. Using analogue materials, I think about the medium itself, while digital images are much more a means to an end. Maybe also because the process does not end with printing an image, it is used at the very early stage of a work.

SvS: When I’m making work that responds to specific buildings or architects I collect a lot of different materials, whether it’s from an archive, or the photographs and rubbings that I make. I see this as a way of amassing a diverse set of representations. Some have the authoured mark of the architect, or the commissioned photographer or architectural illustrator, and some result from my direct contact with a building. What’s exciting about modernist architecture for me is that although it does come from a certain context and time, and is in a sense nostalgic and utopian, it still forms a part of our contemporary experience of our cities. We certainly still live with the legacy of modernism.

I’m mainly drawn to corporate buildings from the mid-twentieth century. Photography played a big role in promoting and presenting these buildings to the public, given that we often don’t experience them in person. These photographs can be quite seductive and utopian in how they represent corporate architecture, even when they are depicting something as mundane as an office space. For me these photographs invert Walter Benjamin’s claim that a work of art loses its aura through mechanical reproduction. Currently I’m drawing from specific elements from these images such as windows and foyers.

What decisions do you make in terms of the structures you make in your work? I’m especially intrigued in the rudimentary quality to your structures, specifically how the tape that holds the prints together is visible. There’s also a simplicity to the wood used at the back of the work which reminds me of cartelami (an ephemeral artifact that dates back to the 17th century, and are made from intricately painted religious scenes on cardboard).

In relation to your use of transfer prints, I interpret this process as a way of translating the original image into a mediated representation, a representation of a representation. Through this they almost lose something from the original photograph.

How do you choose the subject and setting in your work? Most of your recent work focuses on self-portrature, or situations and environments from your studio or home. In the context of coronavirus and social distancing, your work could seem quite romantic, depicting what might be interpreted as an artist working alone in the studio in complete isolation.

What are you currently working on in the studio? And how are you moving forward and adapting your practice given the current situation where a lot of exhibitions are cancelled? Do you have any exhibitions or projects coming up?

Sam van Strien, A Pattern Language (2019), Pastel, laser-cut engraving, paper, plywood, 62x46cm

SR: The simple structures and the composition of the backside of my works evolve around the thought of showing how fragile images are, and how little is needed to give them a physical presence. I have been using wood for a long time – also because I am very interested in its materiality, its inherent recording of time – and therefore, it was a logical step for me to use it for the structures. At the moment, I am in the very beginning of working with representations of found objects, which I think of as possible future artefacts. In a way works that might belong to the same family as the work I made at PADA, when I was there in February.

Can you tell shortly about the support of your rubbings? There might be an interesting relationship in our approach concerning representations and their translation into images. Is the use of plywood a reference to the construction of buildings or are there also other reasons involved? And what role does the laser etching play in the final work?

Self-portraits have always been a part of my praxis – only their dimensions and presence have changed over the past few years. The images on my webpage you are referring to might be a bit misleading as I use many different surroundings for them. My approach emerges from a conglomeration of subjective experiences with culture-historical and art-historical occurrences. In that respect, I am especially interested in the thought that our history and our cultural ideas are shaped through images, which can be repeated, changed, interpreted – and therefore (de-)mystified.

I think this has also a lot in common with the idea of an artist working in the studio, as you describe it. Yes, of course it is a necessity to be there, to think and to physically produce work, but this also quite often leads to a misunderstanding: the work of an artist could never exist without life outside the studio and its surroundings.

The current situation contains of course quite a lot of delays, pending responses, and insecurities, but at least for now life is slowly going back to “normal”. Keeping up what we are doing as artists is the only possible strategy I suppose.

SvS: Yes, I definitely see a relationship in the ways we engage with the backs and supports of our works. My rubbings, like your process with photography, uses individual sheets of paper to create a whole image. The rubbings, when they are brought back to the studio, are glued and assembled on plywood. I was initially using plywood because it is economical, light and warps a lot less than MDF, but I’m also interested in its use in construction and fabrication.

The laser-cut engraving that I inscribe into my rubbings is sourced from photographs of the architectural surfaces I take rubbings from. It is also at a 1-1 scale and correlates to the same position I take my rubbings from. I see this digital process as another tactile experience of the building's surface. Much like your work, it is an abstract and mediated form of representation.

Yes, I totally agree, the only way is to keep going. I’m sure there will be long-term implications on the arts and how things will continue in the future. But it’s always about finding ways to adjust and adapt, and to keep moving forward.

For more information and to see more examples of work visit